Fowler’s Stages of Faith.

1. Introduction:-

When Fowler began writing in 1981, the concept of `faith development’ was a relatively new concept to the study of psychology of religion, but Fowler was able to draw on a rich tradition of Christian Judaic thought and psychological developmental theory[1]. He thus builds on the Judeo-Christian tradition of faith development and the psychological and educational work of Piaget, (Cognitive Structural Development theory), Erikson, (`Stages of Life theory’) and Kohlberg, (`Moral Development Theory’).

Fowler’s theory can be used to understand the development of all religious faiths. Hence his work is not focused on a particular religious tradition or content of belief, but on the `psychological concept of faith (Fowler, 1991:1). Fowler does not concentrate on the contents of faith. He is not suggesting that people change the content of their faith at each stage, but there are differences in styles of faith. This is what Fowler calls the operations of knowing and valuing .

Before Fowler introduces his understanding of the concept `faith’ and the content of each stage Fowler makes a number of cautions, two of these are very important to our understanding of his theory. It will be necessary to keep these cautions in mind in using his theory.

1. The descriptions of stages are `still shots’ in a complex and dynamic process. Hence “the process of `staging’ a person should not be approached with a cubbyhole mentality (Fowler & Keen, 1985:39).”

2. The staging of a person is not an evaluative scale by which to establish the comparative worth of persons. Fowler claims, “ that the stages should never be used for the nefarious comparison or the devaluing of persons (Fowler, 1987:80).” As such the stages are not to be seen as stages in soteriology. There are people at each stage who are persons of serenity, courage and genuine faith

2. Faith

For Fowler faith is a universal quality of human life. Fowler says “Think if you will, of faith as `universal’, as a feature of living, acting, and self-understanding of all human beings whether they claim to be `believers’ or religious or not (Fowler & Keen, 1985:17)”. Belief is “one of the important ways of expressing and communicating faith, but belief and faith are not the same thing (Fowler, 1991:22)”. Faith is deeper than belief, it is more encompassing than the modern understanding of belief as mental assent to some proposition or propositions.

1. When Fowler speaks of faith development he is not simply speaking about religious understandings or beliefs, but the way we shape and form our lives in their totality. Faith includes the passional and the intellectual.

- For Fowler, the term faith has to be viewed as a dynamic, changing, evolving process not as something relatively static. In this way he credits the term with new meaning. In the English language faith is a noun. As such it is viewed as something people either have or they do not have. For Fowler faith is better understood as a verb, ‘a way of being’. Thus faith is an active “mode-of-being-in-relation to another or others in which we invest commitment, belief, love, risk and hope (Fowler & Keen, 1985:17)”. Integrity to the personal journey of faith will involve changing or abandoning previously held beliefs, and commitments.

3. Faith Development

Fowlers concept of faith development is built on two processes which, taken together, constitute, what he calls, the ‘dance of faith development in our lives’. These two processes are conversion and development. Conversion[2] is the radical and dramatic changes that occur in our centres of value, power and master story. This conversion process is the process of transformation and intensification of faith. The second process, that of development, involves a less radical, maturing, similar to the biological process of maturation. Faith development occurs through the ongoing dance of faith involving these twin movements of radical conversion and gradual maturation. Both are integral movements in the dance.

The goal of faith development is not to get everyone to reach the universalizing stage of faith. Fowler is quite clear that people located at each stage can experience a fulfillment of faith. He describes the goal of faith development as being for “each person or group to open themselves , as radically as possible-within the structures of their present stage or transition-to synergy with spirit.

4. Transitions between stages.

The final stage adults may reach varies, yet for each individual there are a number of significant changes that occur in the faith journey. These are the transition points. During these transition points a major change in the basis of our operations of faith occur. Hence the development of faith is not a gentle undemanding stroll through life, involving gradual and imperceptible maturity; but a series of progressive growth stages followed by radical upheavals in our faith operations. Again it needs to be clarified that these upheavals that may result in a person moving to another stage of faith development do not necessarily involve a change in the contents of one’s faith beliefs.

The transition between stages is a difficult and often painful process. It involves relinquishing a previously held way of knowing and valuing. We need to be aware that such transitional changes can be very difficult for the person involved and may seem like being at sea, with a loss of all anchor points[3].

Fowler states that “stage dissolution means enduring the dissolution of a total way of making sense of things. It means relinquishing a sense of coherence in one’s near and ultimate environment. It frequently involves living with a deep sense of alienation for considerable periods (Fowler, 1978:37).” Because it is such a demanding and difficult process to transcend from one means of faith operation to another, Fowler suggests that many people revert to a previous stage rather than face the difficulty or uncertainty of the transition. People may also spend long periods of time[4] and energy transitioning. For this reason some people are best described as being in a transition phase.

5. The Six Stages of Fowler’s Faith Development Theory.

Fowler uses a six-staged progression for faith development which begins around the second year of a child’s life. He does however note the significant faith learning that occurs prior to this age under the heading Primal Faith.

Stage 1: The Intuitive-Projective stage.

At about age two children begin to develop language ability, they can move around freely and investigate and question for themselves. Their lives are a seamless world of fantasy, stories, experiences and imagery. During this stage self is the centre of experience. There are no existing inner structures for sorting and understanding the experiences of the child. Life at this stage is a collage of dis-organized images. These images include the real events of daily life and the imaginary fantasy life of the child.

The children are totally dependent on parents or other adult figures. At this stage authority is based on physical size or the power of external symbols (e.g.- uniforms). Here Children are influenced by the examples, stories and actions of others. Fowler claims the strength of the stage lies in the birth of the imagination, the ability to hold the intuitive understandings and feelings in powerful images and stories.

The dangers of this stage lie in the potential for the child to be overwhelmed by images of terror and destructiveness. The transition to the next stage involves the child’s growing concern to know how things are and to clarify what is real and what only seems that way (Fowler:1981; p122-134).

Stage 2: Mythical-Literal.

To move to this second stage children will necessarily have moved to the cognitive developmental level of `concrete operational thinking’. From this the child can draw stable categories of space, time and causality. For children at this stage the world has now become linear, orderly and predictable (Fowler:1984;p55). At this stage they are better able to think logically. They can take the perspective of someone outside of themselves; this means they can develop a clear sense of fairness. “Faith at this stage becomes a matter of reliance on the stories, rules and implicit values of the family’s community of meaning (Fowler:1984;p55)”.

At this stage the bounds of the child’s world have widened. The primary influence of the family has been added to by the influence of teachers, school, other pupils, television, movies and reading. Because of this the variety of influences affecting the child increase. Here the child typically makes strong associations with `people like us’ and tends to look critically at those who are ‘different’ (Fowler & Keen:1985;p50). During this stage the child begins to “accept the stories, and beliefs that symbolise belonging to her community. Symbols are taken as one dimensional and literal in their meaning. Adults who become stabilised at this stage tend to express the following characteristics.

- A sense of cosmic reciprocity, where what you get out of life is determined by what you put in. This tends to be a simplistic notion of the good get rewarded and the bad get punished, which allows little room for bad things to happen to essentially good people. Adults at this stage may bargain with `God’ saying – I will behave in such and such a way to ensure your blessing.

- Tend to define people according to their roles and actions, rather than being able to differentiate the role from the person performing it[5].

- Adults at this stage tend to engage in little personal reflection on themselves or others. People are taken at face value, and little thought is given to what may influence them to behave in the way they do.

- Adults at this stage tend to use narrative stories as their primary way of communicating their meaning to others. As yet they are unable to draw abstract conclusions about the general meaning of life.

Although powerfully influenced by narrative and story people at this stage cannot stand back and view the events from the position of a neutral observer. Here they lack the ability to reflect on either their own position or the position of others from a ‘value free’ position.

Stage 3 Synthetic-Conventional.

By the term `Synthetic’ Fowler means that at this level the individual attempts to draw together the disparate elements of his/her life into an integrated identity. The term `Conventional’ indicates that the values and beliefs they hold are derived from a group of significant others and for the most part are accepted without being examined.

Individuals at this stage are acutely tuned to the expectations and judgements of others, and as yet do not have a sure enough grasp of their own identity or faith in their own judgment to construct and maintain an independent perspective. Consistent with this a person at this level may hold deep convictions, yet typically they have not critically examined these. Fowler states: – “At stage 3 a person has an ideology, a more or less consistent clustering of values and beliefs, but he or she has not objectified these for examination and in a sense is unaware of having them (Fowler:1981:173)”.

This leads us to the significant danger of this stage, which is that the expectations and beliefs of others can be so deeply internalised that later autonomy of judgement and action can be jeopardized.

At this stage an individual may be involved in many different roles or ‘theaters of action’. In each of these there may be different views, beliefs, ideologies and ways of operating. This is coupled with the fact each of these roles may place different expectations on the individual. Because self-identity is so integrally tied to the expectations and judgements of others at this level such expectations of others weigh heavily on them. Fowler suggests that individuals may employ one of two strategies to cope with the dissonance of expectations and judgements placed on them in their different roles. The first of these he labels ‘Compartmentalizing’. Under this strategy the individual behaves within the expectations of one group when they are with them and behaves under the expectations of another group when with them. The other strategy to cope with this dissonance is to form a personal ‘hierarchy of authorities’, whereby the expectations and authority of one group is seen as primary and others must fall below these.

People at this stage are generally committed workers and servers who have a strong sense of loyalty to their church. They are not typically innovative thinkers who would not normally be interested in analytical approaches to faith.

In a church situation Fowler describes people at this stage as “looking for a relationship with God and with the important persons of their lives in which they feel that they are living up to the expectations these important others have of them (Folwer:1987;p87)”. They have a strong sense of the church as an extended family; even a romanticized extended family, where the important thing is to be there to support each other. Because of this conflict and controversy are threatening to them. They will tend to work for harmony and would often prefer to bury conflict rather than allow it to surface and potentially destabilise the sense of community which is so important to them. As they come to church and take part in the service they are looking for, all be it unconsciously, a sense of warmth and connectedness.

Jack Pressau in his book -‘I’m Saved, You’re Saved – Maybe’. takes Fowler’s stages and looks at them from a Soteriological[6] perspective. In this analysis he speaks of the Synthetic-Conventional stage of faith as having that ‘arrived feel to it’. Religious groups that reinforce this ‘arrived feel’ can be fast growing.

Such churches, religious groups or ideological groups appeal to individuals operating at the Synthetic-Conventional stage. To quote Preassau they provide a ‘walled in’ religious commitment, which can be reassuring to the stage 3 person

“The factors that contribute to the breakdown of a Synthetic-Conventional stage may include: serious clashes or contradictions between valued authority sources; marked changes by officially sanctioned leaders, or policies or practices previously deemed sacred and unbreachable, or the encounter with experiences or perspectives that lead to critical reflection on how one’s beliefs and values have formed and changed, and on how relative they are to one’s particular group or background ( Fowler in Stokes:1983;p188)”.

Stage 4 Individuative-Reflective

The transition from stage 3 to stage 4 is frequently a protracted affair, and one that can be quite destabilizing and dis-orienting for the person involved. The move to a Individuative-Reflective stage is “occasioned by a variety of experiences that make it necessary for persons to objectify, examine, and make critical choices about the defining elements of their identity and faith (Fowler:1984;p62).”

During the transition from Synthetic-Conventional to Individuative-Reflective two key processes occur. Fowler describes these as:

1. There must be a shift in the sense of the grounding and orientation of the self. From a definition of self derived from one’s relations and roles and the network of expectations that go with them, the self must now begin to be and act from a new quality of self-authorization. There must be the emergence of an “executive ego”- a differentiation of the self behind the personae (masks) one wears and the roles one bears, from the composite of roles and relations through which the self is expressed.

2) There must be an objectification and critical choosing of one’s beliefs, values, and commitments, which come to be taken as a systemic unity. What were previously tacit and unexamined convictions and beliefs become matters of more explicit commitment and accountability (Fowler:1984;p62).”

The latter this transition occurs in adult life the more difficult (painful) the transition tends to be. When it is delayed until an individuals thirties or forties, “it can be quite disturbing to the whole network of roles and relations they have formed. Sometimes people will work through only one of the two shifts we examined above.

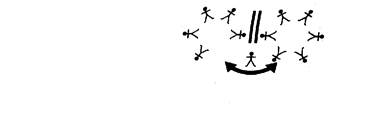

At stage 4, as the illustration indicates, the individual begins to emerge from the previous encircling influence of significant others and significant groups. People at this stage tend to hold themselves, and others, more accountable for their own “`authenticity, congruence, and consistency’ (Fowler & Keen:1985;p70). It is important for people at this stage that they take responsibility for their beliefs, actions and decisions. They no longer tolerate following the crowd. The making of their own decisions becomes increasingly important to them.

At the Individuative-Reflective stage, relationships are built on a sense of personal autonomous identity and a respect for other’s autonomous identity. At this level Fowler claims that “a persons reference group(s), for purposes of identification and inclusiveness in calculating moral responsibility may be quite wide. There is at least a formal recognition of the diversity and relativity of different group interests and an implicit recognition of the obligation to take the claims and perspectives of other groups (classes, ethnic or racial groups, national communities, religious communities and the like) into account over against one’s own. (Fowler & Keen:1985;p72) .”

At the Individuative-Reflective faith stage symbols, myths and ritual are found “meaningful if they can be translated into usable concepts”. Here their usefulness is limited to the extent that they help the individual to make personal meaning and `sense’ of their beliefs, actions, position and decisions. The rituals, symbols and myths are useful because of their perceived underlying meaning. They can be accepted as illustrations of truth.

The danger of this stage is, as with the other stages, an over-emphasis on its strengths. People at stage 4 typically see themselves as ‘self sufficient, self starters, self-managing and self-repairing units. It is just this over potential of the place of self as against the need for community and relationships which can undermine the strengths of the stage. The over emphasis on the place of self can lead the individual into one of two distorted views.

1. They can fall into an sense of self-aggrandizing, in this state of over inflation they can end up allowing themselves privileges and moral leeway that later prove to be destructive of either themselves, their relationships, or their values which they have ended up taking for granted.

2. There dependence on self can lead to a deflation and excessive criticism and despair about self. (Fowler:1987;p91-92).

People at this stage do not sit easily with a leadership structure that requires them to be dependent upon it. They are less impressed by a leaders special training, ordination or the like. They want a leadership structure that acknowledges and respects their personal positions and allows room for them to contribute to the decision making of the group. They are more comfortable with criticism and debate, even disagreement within the group. Conflict and disagreement that was once seen as potentially threatening is now viewed more positively, perhaps even relished.

Stage 5 Conjunctive [7]Faith.

The experience of reaching mid-life can mark the beginning of a movement to a new stage of faith development -the Conjunctive stage. Here, Fowler says the “ firm boundaries of the previous stage begin to become porous and permeable.

The conscious ego must develop a humbling awareness of the power and influence of aspects of the unconscious on our reactions and behaviour. This transition coincides with a realization of the power and reality of death, the feelings of growing and looking older, ones own children reaching teenage or adult years, and an awareness that there are aspects of our own identity that we will not be able to change. Fowler sums up the necessary life experience to begin to transition into this stage as having learnt” by having our noses rubbed in our finitude (Fowler:1987;p93)”. What is formed is a multi-dimensional self knowledge.

Fowler suggests that many adults never reach stage 5.

There are 4 hallmarks, listed by Fowler, of the conjunctive stage of faith development.

1. An awareness of the need to face and hold together several unmistakable polar tensions in one’s life: the polarities of being both old and young and of being both masculine and feminine. Further it means integrating the polarity of being both constructive and destructive and the polarity of having a conscious and a shadow self.

2. Conjunctive faith brings a felt sense that truth is more multiform and complex than most of the clear, either/or categories of the Individuative stage can properly grasp. In its richness, ambiguity, and multidimensionality, truth must be approached from at least two or more angles of vision simultaneously. Conjunctive faith comes to cherish paradox and the apparent contradictions of perspectives on truth as intrinsic to that truth. People at this level will “resist a forced syntheses or reductionist interpretations and are generally prepared to live with ambiguity, mystery, wonder, and apparent irrationalities (Fowler & Keen:1985;p81)”.

3. Conjunctive faith moves beyond the reductive strategy by which the Individuative stage interprets symbol, myth, and liturgy into conceptual meanings…….Conjunctive faith gives rise to a second naiveté, a postcritical receptivity and readiness for participation in the reality brought to expression in symbol and myth.

4. A genuine openness to the truths of traditions and communities other than one’s own. This openness, however, is not to be equated with a relativistic agnosticism (literally a not knowing)……Conjunctive faith exhibits a combination of committed belief in and through the particularities of a tradition, while insisting upon the humility that knows that the grasp on ultimate truth that any of our traditions can offer needs continual correction and challenge. This is to help overcome blind spots as well as the tendencies to idolatry (the over identification of our symbolization’s of transcending truth with the reality of truth) to which all our traditions are prone. (Fowler:1984;p65-66).”

In describing people of conjunctive faith, Fowler has, stated that these individuals are “not likely to be `true-believers’, in the sense of an undialectical, single-minded, uncritical devotion to a cause or ideology…….such people know that the line between the righteous and the sinners goes through the heart of each of us and our communities, rather than between us and them (Fowler:1984;p67).”

Again as with all the stages their inherent weakness are the shadow side of their strengths. Fowler is quick to add that because of each stages weakness there is a need to remain open to the strengths and correction of people at other stages.

1. “People can develop a deep sense of cosmic aloneness or homelessness.

2. The dark side of their awareness of God’s revelation lies in a deepened appreciation of the otherness and the non-availiability of God.

3. The dark side of their receptiveness to the witness and the truth of other traditions can be a subdued sense of imperative to in `evangelization’.

4. The dark side of their awareness of being enmeshed in vast and complex systems can be a sense of paralysis and a retreat into a private world of spirituality……an immobility (Fowler:1987;p94-95)”.

Stage 6: – Universalizing

Two key transitions occur in the move to a universalizing faith. Firstly there is the “decentration from self” here the self is moved from the centre or focus in the individuals life. As illustrated by the diagram above, the image of self is removed. The is coupled with a continued widening of the circle of “those who count.” Here the individual is able to know the world through the eyes of the other in their experiences of persons, classes, nationalities, and faiths quite different from one’s own.

The second move is a move in the things an individual values and the sense of valuation they receive from them. “As people have moved through the stages of faith there has been a successive widening of the groups and individuals who’s values become a matter of their concern as well. “This process reaches a kind of completion in Universalizing faith, for there a person decenters in the valuing process to such an extent that he/she participates in the valuing of the creator and values other beings – and being- from a standpoint more nearly identified with the love of Creator for creatures than from the standpoint of a vulnerable, defensive, anxious creature (Fowler:1984;69).”

Fowler acknowledges that is only the rare individual who reaches this stage of faith development. The examples that he uses of people who have attained an equilibrated stage six level include- Mother Teressa, Dietrick Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King, Mahatma Ghandhi and Jesus. Each of these are individuals who have given up the `self’ for the sake of the community.

At each successive stage the ‘circle’ of people who are significant to the individual increases. Here at this final stage Fowler says -“it means knowing the world through the eyes and experiences of persons, classes, nationalities and faiths, quite different from one’s own (Nipkow:1991;p68)”.

Bibliography.

Berryman J. (Ed) Life Maps: Conversations on the Journey of Faith – James W Fowler & Sam Keen

Word Books; 1987

Dystra C. & Parks S. Faith Development and Fowler; Religious Education Press Birmingham Alabama 1986

Fowler J. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning: Harper &

Row; San Francisco 1981.

Fowler J. Becoming Adult, Becoming Christian: Adult Development and Christian Faith. Harper & Row;

San Francisco 1984

Fowler J. Faith Development and Pastoral Care; Fortress press; Philadelphia 1987

Fowler J. Weaving the New Creation: Stages of Faith & the Public Church. Harper & Row; San Francisco 1991

Fowler J.; Nipkow E.; & Schweitzer (eds) Stages of Faith and Religious Development: Implications for Church,

Education and Society. Crossroad; New York 1991

Fowler J. Stages of faith: Reflections on a Decade of Dialogue: Christian Educational Journal. Vol XIII, Number 1

Autumn 1992.

Parks S. The Critical years: the Adults Search for a Faith to Live by. Harper & Row; San Francisco

1986

Peck M. Further Along the Road Less Traveled: Simon & Schuster; New York 1993.

Stokes K (ed) Faith Development in the Adult Life Cycle: W.H. Sadlier; New York 1983

[1] Fowler’s own background is as a theologian, ethicist and developmental psychologist.

[2] Fowler defines conversion as “ a significant recentering of one’s previous conscious or unconscious images of value and power, and the conscious adoption of a new set of master stories in the commitment to reshape one’s life in a new community of interpretation and action (Fowler:92;p16).” Fowler clearly distinguishes between conversion and stage transition. Conversion is principally about the `contents’ of faith ; where stage transition is about the `operations of faith ( i.e the operations of knowing, valuing and committing).

[3] Parks describes the process as being shipwrecked.

[4] One theological lecturer in the area of pastoral care suggested that an average transistion between adult faith development levels takes around two years. During this time the person feels that their faith is very tenuous, under threat, or evolving.

[5] A typical example of this would be taking our son, Chris, to his grandfathers bowling club in which his headmaster is a member. When Chris saw the headmaster there he couldn’t conceive that a headmaster could also be a friend of his grandfathers and respond to him in a way other than in his role as a headmaster.

[6] A soteriological perspective looks at what is necessary for salvation from a Christian persepctive. Fowler states – “ it often comes as a challenge for persons to understand that stages of faith are not stages in salvation, at least if salvation is understood as the assurance of eternal life with God in heaven. These are not stages in soteriology; there is not an `X’ stage one must attain in order to be in a right relationship with God. In fact, one can be `in Christ’ or stand in a saving relation to God while being operationally described by any of the faith stages. Similarly, one can exhibit a relatively high stage of faith development and be marked by doubt, alienation, and anxious absorption in self-preservation (Fowler:1992;p19).”

[7] Fowler describes the history of the term `conjunctive ‘ in the following way. “ This name can be traced to Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464), whose greatest work, de Docta Ignorantia, developed the idea of God as the coincidentia oppositorum – `the coincidence of opposities’ – the being wherein all opposites and contradictions meet and are reconciled. Carl Jung adapted this idea in many of his psychological writings on religion, altering the term to the coniunctio oppositorum – the conjunction of opposites. In some of Fowler’s earlier descriptions of the stages the fifth stage was titled `Paradoxical-Consolidative’.